It was fifty years ago today that the seething resentment of black Americans toward the glacial pace of reversing racial injustice and urban black poverty exploded at its greatest scale up to that point. It could have happened in large cities such as New York, Chicago or Los Angeles, and it could have happened in any city in the South.

Instead, it happened in Newark, New Jersey.

Newark in 1967 was a working-class city that was seeing its white population move to the Essex County and Morris County suburbs to the west for houses on larger lots and the new shopping centers sprouting up along the highways. Blacks had become the majority of the city's population, and even the few who could leave were denied newer housing in suburbia. (Black suburbanization took root instead in inner suburbs, such as East Orange, which was also being abandoned by whites, as well as in neighborhoods in nearby towns like Montclair.) Blacks still accounted for only 11 percent of the Newark police force, and they were denied the best jobs in the municipal government, still dominated by Irish and Italian politicians. Mayor Hugh Addonizio, who would be the last non-Hispanic white mayor of Newark, seemed utterly clueless to the social discord.

In July 1967, as young people in San Francisco were having love-ins, the situation in Newark finally blew up. Two Italian-American policemen, John DeSimone and Vito Portrelli, stopped and arrested a black taxi driver, John Weerd Smith, after he drove past their patrol car improperly on Fifteenth Avenue in the Central Ward, and they took him to the local precinct station. Residents of a public housing project (one of those high-rise brick-box projects that are a testament to how providing shelter for the poor is an afterthought in American housing policy) across the street from the precinct station saw them dragging an incapacitated Smith into the precinct. Though Smith was brought to a nearby hospital, rumors began that he had died in police custody. Angry residents confronted police at the station, and the trouble began almost immediately.

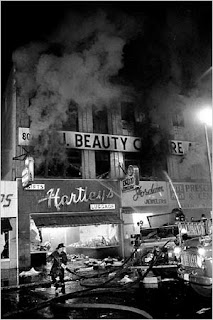

The riot, which originated in the Central Ward, spread to other parts of town and pitted the police and the rioters in a full-scale urban war. Even Broad Street (above), the city's main downtown thoroughfare, was not spared. New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes was forced to send in the state militia, and the tensions escalated. The heavy-handed reactions by the police and the militiamen made some people wonder why the rioters were being called the aggressors.

The presence of the militia, or the National Guard, made Newark look more like Saigon than an American city.

The fires and violence caused by the insurrection leveled whole neighborhoods. Numerous businesses were wiped out. Twenty-six people were dead and 727 were injured by the time when it was all over. And, lest anyone thought it was just a conflict between the powerful and the powerless, black retailers took the initiative to scrawl the words "SOUL BROTHER" on their front windows to deter black rioters from looting black businesses. The racial lines had indeed been drawn.

White Newarkers, then 46 percent of the city's population, staged their own revolt - by packing up their cars and accelerating the white flight to the suburbs. Among them were one Wilbur Christie and his wife Sondra, the parents of the current New Jersey governor, who moved to suburban Livingston.

The city went through a long period of decline, as the industries that supported it gradually faded away, leaving the Prudential insurance company, founded in Newark in 1875, still anchoring the downtown business district. Newark has been on the rebound lately. Broad Street hasn't looked as clean as it does now in years. There are new light-rail trains and a new streetcar line connecting the old Lackawanna railway station on Broad Street run by NJ Transit and the old Pennsylvania Station now serving NJ Transit trains, Amtrak intercity trains, and Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) trains to New York. There's a burgeoning arts community, along with the New Jersey Performing Arts Center and an arena where the New Jersey Devils hockey team play. The building once occupied by Hahne's, a department store that has long since gone out of business, has been restored, with housing and retail (including a Whole Foods). And the population, which bottomed out at 273,546 people in 2000, has risen to 281,764 - above even 1990 levels. Many of those new residents, no doubt, moved to the new housing that replaced the slum on Fifteenth Avenue (below).

But Newark is still down in the dumps. Violent crime is an everyday occurrence. The school system leaves a good deal to be desired. A minor-league ball team failed, and its stadium is an empty shell. Vacant lots are visible both in the neighborhoods and in the downtown area. And when you walk in either direction on Market Street away from Broad Street, the scenery is pretty shabby . . . and the sight of the abandoned and once-grand Paramount Theater is heart-breaking. A seventy-old man who remembers the glitz and glitter of downtown Newark that he experienced as a ten-year-old boy, returning to the city after sixty years, wouldn't recognize Market Street today, least of all its intersection with Washington Street.

Note the absence of live people on the sidewalks.

The building on the right is the site of Bamberger's, once northern New Jersey's premier department store, which later branched out to the new malls in the suburbs. Macy's bought the Bamberger's chain, eventually changed the name of the stores to Macy's, and closed the original Newark store in 1992; the building is still waiting for a rehabilitation. I recently showed my friend Clarisel around downtown Newark, and when we got to the intersection of Market and Washington Streets, well . . . I was so embarrassed, it would have been rude for me to voice my true feelings. I'm not from Newark, but my uncle - my father's brother-in-law - is, and he grew up in the old Irish neighborhood in the North Ward, where the late Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. came from. My father went to St. Benedict's Preparatory School just a few blocks from downtown. My family remembers going to Bamberger's every Christmas, where they had snow villages and a slide along Santa Claus's chair not unlike the one in the movie A Christmas Story. I don't remember the Newark of old; I only hear stories about a place I will never know for as long as I live.

I don't blame the rioters for the decline of Newark. I blame America's asinine urban development policy that champions tract housing and highway shopping complexes over traditional cities, as well as the de-industrialization of America that sent all of the good jobs to China. I also blame an anti-urban, anti-poor, anti-non-white attitude among our leaders that allowed cities like Newark to deteriorate. Newark's slow pace of revival is proof people that, as in the case of racial equality, progress has been made but we still have a long way to go.

John Weerd Smith later declared that if he hadn't been arrested and mistreated by the police, something else would have inevitably happened to spark an insurrection.

The 1967 Newark riot was the worst American urban civil disturbance of the 1960s . . . until Detroit blew up less than two weeks later.

No comments:

Post a Comment